Reviewed June 30, 2006.

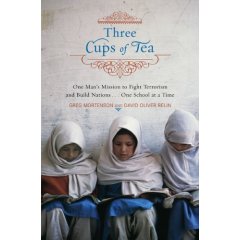

Viking, New York, 2006. 338 pages.

Available at Sembach Library

(MCN 371.822).

Greg Mortenson’s story began

when he failed to reach the top of

K2,

the

second highest mountain in the world.

On

the way down, he took a wrong turn and wound up collapsing in a small

village

in northern

Pakistan.

The kind people took him in and cared for

him.

When “Dr. Greg” got better, he

looked at the village.

He saw the girls

trying to learn outdoors, in wind and weather.

He

made a rash promise to come back and build them a

school.

It was

extremely difficult to

keep that promise, with very little money. He

tried sending letters to rich people, but 500 letters

only got one

response. Eventually, he found a sponsor

through his mountaineering connections, someone who had also seen the

need in

that part of the world.

So Dr. Greg

went back and

took on the adventure of buying the materials for a school and getting

them to

the remote village. After buying the

goods, he found many other people wanting him to build the school in

their

villages. When he finally reached the

village where he had promised to return, he found that he needed to

build a

bridge before he could get the supplies into the village.

The book

tells of Mortenson’s

continued efforts. After he went back to America

to try to raise money for a bridge, he lost his job, his girlfriend,

and his

apartment. But he kept going, and

eventually one thing led to another, and he is now the head of Central

Asia

Institute, which builds schools all over remote Pakistan

and Afghanistan. The schools allow both girls and boys to be

educated, with whole new possibilities open to them.

Greg

Mortenson is not a

Muslim, but he works with Muslims and respects their beliefs. When a village leader issued a fatwa

against him because he hadn’t paid a bribe to build a school, the case

was

tried in shariat court, and the fatwa was overturned.

“ ‘It was a very humbling victory,’ Mortenson

says. ‘Here you have this Islamic court

in conservative Shia Pakistan offering protection for an American, at a

time

when America is holding Muslims without charges in Guantanamo, Cuba,

for years,

under our so-called system of justice.’”

His work

began years before

September 11th, 2001, but naturally after that the climate

changed

drastically. A mullah was scheduled to

speak at a school dedication a few days later.

Part of his speech included, “These two

Christian men have come halfway around the world to show our Muslim

children

the light of education….I request America to look into our hearts, and

see that

the great majority of us are not terrorists, but good and simple people. Our land is stricken with poverty because we

are without education. But today,

another candle of knowledge has been lit. In

the name of Allah the Almighty, may it light our way

out of the

darkness we find ourselves in.”

After 9/11,

Mortenson’s work

got more attention. He told a

congressman, “I don’t do what I’m doing to fight terror.

I do it because I care about kids. Fighting

terror is maybe seventh or eighth on

my list of priorities. But working over

there, I’ve learned a few things. I’ve

learned that terror doesn’t happen because some group of people

somewhere like Pakistan

or Afghanistan

simply decide to hate

us. It happens because children aren’t

being offered a bright enough future that they have a reason to choose

life

over death.”

In another

comment he said,

“People in that part of the world are used to death and violence. And if you tell them, ‘We’re sorry your

father died, but he died a martyr so Afghanistan could be free,’

and if

you offer them compensation and honor their sacrifice, I think people

will

support us, even now. But the worst thing

you can do is what we’re doing—ignoring the victims.

To call them ‘collateral damage’ and not even

try to count the numbers of the dead. Because

to ignore them is to deny they ever existed, and

there is no

greater insult in the Islamic world. For

that, we will never be forgiven.”

A Pakistani

friend also had

good insight on the situation. “Osama,

baah! Osama is not a product of Pakistan or Afghanistan. He is a creation of America. Thanks to America, Osama is in every

home. As a military man, I know you can

never fight and win against someone who can shoot at you once and then

run off

and hide while you have to remain eternally on guard.

You have to attack the source of your enemy’s

strength. In America’s case, that’s not

Osama or

Saddam or anyone else. The enemy is

ignorance. The only way to defeat it is

to build relationships with these people, to draw them into the modern

world

with education and business. Otherwise,

the fight will go on forever.”

An Afghani

warlord also spoke

with eloquence. “ ‘Look here, look at

these hills.’ Khan indicate the

boulderfields that marched up from the dirt streets of Baharak like

irregularly

spaced headstones, arrayed like a vast army of the dead as they climbed

toward

the deepening sunset. ‘There has been

far too much dying in these hills,’ Sadhar Khan said, somberly. ‘Every rock, every boulder that you see

before you is one of my mujahadeen,

shahids, martyrs, who sacrificed

their

lives fighting the Russians and the Taliban. Now

we must make their sacrifice worthwhile,’ Khan said,

turning to face

Mortenson. ‘We must turn these stones

into schools.’”

At the start

of the book, the

co-writer, David Oliver Relin, says, “As a journalist who has practiced

this

odd profession of probing into people’s lives for two decades, I’ve met

more

than my share of public figures who didn’t measure up to their own

press. But at Korphe and every other

Pakistani

village where I was welcomed like long-lost family, because another

American

had taken the time to forge ties there, I saw the story of the last ten

years

of Greg Mortenson’s existence branch and fork with a richness and

complexity

far beyond what most of us achieve over the course of a full-length

life.”

“As I found

in Pakistan,

Mortenson’s Central Asia Institute does, irrefutably, have the results. In a part of the world where Americans are,

at best, misunderstood, and more often feared and loathed, this

soft-spoken,

six-foot-four mountaineer from Montana

has put together a string of improbable successes.

Though he would never say so himself, he has

single-handedly changed the lives of tens of thousands of children, and

independently won more hears and minds than all the official American

propaganda flooding the region.

“So this is a

confession: Rather than simply reporting

on his progress, I want to see Greg Mortenson succeed.

I wish him success because he is fighting the

war on terror the way I think it should be conducted.

Slamming over the so-called Karakoram

‘Highway’ in his old Land Cruiser, taking great personal risks to seed

the

region that gave birth to the Taliban with schools, Mortenson goes to

war with

the root causes of terror every time he offers a student a chance to

receive a

balanced education, rather than attend an extremist madrassa.”

Relin has

communicated this

vision, and completely won me over as well. I

almost cheered when I saw this book had made The New

York Times

Bestseller List. I hope that many, many

people

hear about what Mortenson is doing and support his work.

Fighting evil with good is wondrously more

effective than bombs.

Besides that,

along with all

the inspiration, you’ll get a fascinating, gripping, and well-told

story. How can you go wrong?

You can find

out about

Central Asia Institute at www.ikat.org.

Copyright © 2006 Sondra

Eklund. All rights reserved.

-top of page-

Book Reviews by Sondra Eklund

Book Reviews by Sondra Eklund

Book Reviews by Sondra Eklund

Book Reviews by Sondra Eklund