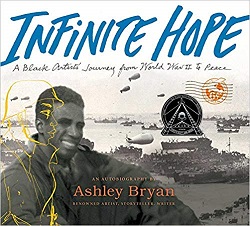

Infinite Hope

Infinite HopeA Black Artist’s Journey from World War II to Peace

A Caitlyn Dlouhy Book (Atheneum Books for Young Readers), 2019. 108 pages.

Review written January 20, 2020, from a library book

Starred Review

A 2020 Capitol Choices selection

2020 Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honor

2020 Sonderbooks Stand-out:

#3 Longer Nonfiction for Children and Teens

Infinite Hope is visually stunning. The extra large pages are filled with sketches, copies of letters, and photographs, all from the author’s service during World War II.

I was relieved when I realized that all the handwritten letters are transcribed into print. There’s not a whole lot to read on each page, but there is so much to see.

Ashley Bryan is a distinguished Black writer and illustrator of children’s books. World War II came as he was getting started in art, having won a scholarship to art college. His art career was interrupted when he was drafted to serve in World War II, but he spent the whole war sketching what he saw. This book tells his story, illustrated by the actual sketches.

It’s a story of discrimination. Ashley Bryan wasn’t used to discrimination, having grown up in the Bronx, but that was how things worked in the U. S. Army. When they got to Europe, though, they found something different.

The Scottish people were warm and welcoming to all of us Black GIs. For some of the Southern men in our company, this was their very first experience of open, friendly encounters with white people. The Scots offered us unquestioned acceptance as equals, a level of immediate friendship that we rarely received at home.

This did not please our white company officers, who were determined to enforce the US Army policy of segregation. Their general attitude that Blacks were beneath them – that “we do not treat them like that!” prevailed. So they began to circulate terribly demeaning stories about Black people, saying that we would hurt them, that we had tails that would come out at night. Their goal was to make the Scottish people fearful so that they would avoid us.

To the officers’ great annoyance, their efforts did not change the way the people of Glasgow viewed us. The Scots did not have the institution of racism – they weren’t socialized against Blacks. Despite the officers’ attempts to sway them, the Scots trusted our actions and friendliness rather than the officers’ words.

Ashley Bryan even got permission to take classes at the Glasgow School of Art.

The fellows in my company never held it against me that I was free to leave camp to go to the art school, even when they were restricted. I had always shared my artwork with them and had helped some of them write letters to loved ones at home, so they were glad for me, glad that I had a chance to get better at something I loved. For while they were playing cards or dice, I was drawing, drawing, drawing. They also took it as my way of going over the head of our company officer, and cheered me on.

He tells about taking part in D-Day and its aftermath – and throughout it all, he kept on sketching. He stored all those sketches after the war (having regularly mailed batches back to his parents), and now was finally ready to pull them out. I like when he talks about preparing the sketches for an exhibit and turning some into paintings.

Fifty years ago, those paintings would have been dark – grays and blacks. But in really looking at those sketches now, I saw a beauty there – the beauty of the shared human experience. And I was able to face these sketches, face these memories and emotions, and turn them into the special world created by the men. I think of the men who were in the unit with me – I had such respect for what they could do, things I was so inept at. I remember their generosity toward me. I can never give them more than they gave me, so I would paint them in full color, filled with the vibrancy and life I had put into my garden paintings. I was ready.

I chose to paint from sketches of the soldiers playing cards or dice. This was a world they created, sheltered from the segregation and racism they endured. Sheltered from all sorts of war. I look now at the color, open form, and rhythm of those paintings. To me, they seem to have come out of my Islesford garden paintings rather than the drab colors of Omaha Beach! They have that surprise of discovery and invention that comes from seeing a well-known theme anew. They open the door to many other unexpected possibilities – because what is life, if not a voyage of endless discovery.

And so Ashley Bryan takes his sketches and inside story of World War II and makes it a thing of beauty and hope.