Sonderling Sunday – Momo, A Usual Dispute

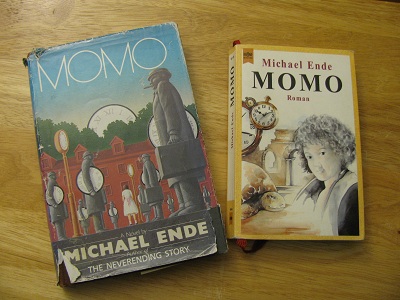

It’s time for Sonderling Sunday! That time of the week when I play with language by looking at the German translation of children’s books, or in this case, the English translation of a German children’s book. This week, I’ll be back with the German classic, Momo, by Michael Ende.

I’ve been busy this weekend, with Sunday my only day off work, so I don’t have a lot of time to spend. But I didn’t want to skip Sonderling Sunday this week, since I missed last week. So here goes!

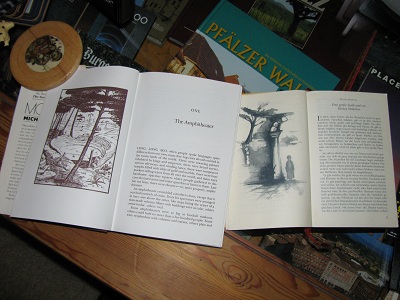

Last time I looked at Momo, I left off in the middle of Chapter Two, which in German is Eine ungewöhnliche Eigenschaft und ein ganz gewöhnlicher Streit, “An unusual character and a completely usual dispute.” In English, it’s just called “Listening.” We finished the “unusual character” part last time, and now we’re on page 12 in the English version and Seite 21 auf Deutsch. I will dive in with some fun phrases, which I hope will motivate readers to look for this incredibly good book.

auf den Tod zerstritten hatten = “quarreled violently”

(literally, “to the death divided had”)

in Feindschaft lebten = “live at daggers drawn”

(“in enemity live”)

geweigert = “objected”

This one isn’t translated directly, so I’ll do the whole sentence:

Nun sa?en sie also im Amphitheater, stumm und feindselig, jeder auf einer anderen Seite der steinernen Sitzreihen, und schauten finster vor sich hin.

= “So there the two men sat, one on each side of the stone arena, silently scowling at nothing in particular.”

(“Now sat they in the amphitheater, silent and hostile, each on another side of the stone rows of seats, and looked darkly at each other.”)

ein starker Kerl = “a strapping fellow”

mit einem schwarzen, aufgezwirbelten Schnurrbart

= “with a black mustache that curled up at the ends”

mager = “skinny”

verstockt = “stubborn as a mule”

puterrot vor Zorn = “puce with rage”

ballte die Fäuste = “clenching his fists”

Aber da siehst du, Momo, wie er lügt und verleumdet!

=”There you are, Momo, you see the dirty lies he tells?”

(“But there you see, Momo, how he lies and slanders!”)

Kragen = “scruff of the neck” (“collar”)

Spülwasserpfütze = “pool of slops” (“rinsing-water-puddle”)

seiner Spelunke = “lousy inn of his” (“his dive”)

ersaufen = “drown”

Beschimpfungen = “insults”

Schandtat = “assaulting”

Ninos ganzes Geschirr zu zertrümmern = “tried to smash all his crockery”

Krug = “jug”

geschmissen = “threw”

Urgro?vater = “great grandfather”

Schiefen Turm von Pisa = “Leaning Tower of Pisa”

knallroten = “bright red”

Wer nichts wird, wird Wirt. = “This inn is out.”

(I don’t get it, but it comes out literally as: “Who nothing will, will Host.”)

Ah, jetzt wirst du bla?! = “Ah, that’s floored you, hasn’t it!”

(“Ah, now you are pale!”)

Du hast du mich nämlich nach Strich und Faden übers Ohr gehauen

= “You cheated me right, left, and center”

(“You have me namely after line and thread over ear carved”)

Umgekehrt wird ein Schuh draus! = “You’ve got it the wrong way around.”

(“The other way around is a shoe out!” [“The shoe’s on the other foot”?])

hereinlegen = “cheat”

gelungen = “succeed”

geschicktes Feilschen = “skillful haggling”

Pappdeckel = “cardboard backing”

Übervorteilte = “outsmarted”

Getauscht ist getauscht! = “A deal’s a deal.”

Ein Handschlag gilt unter Ehrenmännern! = “We shook hands on it, after all.”

(“A handshake applies under honorable men.”)

jubilieren = “warble”

And to end off the chapter:

Und wer nun noch immer meint, zuhören sei nichts Besonderes, der mag nur einmal versuchen, ob er es auch so gut kann.

=”Those who still think that listening isn’t an art should see if they can do half so well.”

(“And who now still always thinks, listening is nothing special, they wish only once to try, if they it also can do so well.”)

Now we know what to call all those Beschimpfungen we learned from The Order of Odd-Fish. See if you get a chance to use some of these phrases this week!