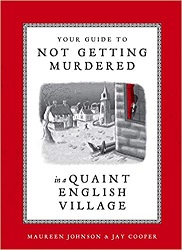

Review of Your Guide to Not Getting Murdered in a Quaint English Village, by Maureen Johnson and Jay Cooper

Your Guide to Not Getting Murdered in a Quaint English Village

Your Guide to Not Getting Murdered in a Quaint English Village

by Maureen Johnson and Jay Cooper

Ten Speed Press, 2021. 128 pages.

Review written November 27, 2021, from a library book

Starred Review

A couple years ago, I read a column by Maureen Johnson with this same theme that got me laughing hard. If you like British cozy mysteries at all (and I’m a fan), then her words ring true. Every one of the scenarios you’ll find in this book sounds familiar to me – I’m sure I’ve read books where people died in these ways in a quaint English village.

Here’s the premise, given in “A Note to the Gentle Reader” at the front of the book:

You’ve finally taken your dream trip to England and have seen London. Then the trouble begins:

You’ve decided to leave the hustle and bustle of the city to stretch your legs in the bucolic countryside of these green and pleasant lands.

You’ve read the books and watched the shows. You know what to expect: You’ll drink a pint in the sunny courtyard of a local pub. You’ll wander down charming alleyways between stone cottages. Residents will tip their flatcaps at you as they bicycle along cobblestone streets. It will be idyllic.

The author respectfully suggests you put aside those fantasies. It is possible that you will find yourself in a placid and tedious little corner of England; it is just as possible you will end up in an English Murder Village. You will not know you are in a Murder Village, as they look like all the other villages. When you arrive in Shrimpling or Pickles-in-the-Woods or Wombat-on-Sea or wherever it is, there will be no immediate signs of danger. This is exactly the problem. You are already in the trap.

However, if you fail to follow the author’s advice and go to the countryside anyway, she has a bookful of things for you to watch out for – ways you may get murdered if you are not wary.

These ways of being murdered are cheerfully and gruesomely illustrated by Jay Cooper.

The focus is on the Village and on the Manor right outside the village, with their separate realms for bumping people off.

Some examples:

Under “THE VILLAGE POND”:

Those ducks didn’t get fat on bread.

under “THE VILLAGE HALL”:

Oh you giggled at Edith’s sonnet? Sounds like someone’s about to be found clubbed to death with a typewriter, their mouth stuffed full of poems.

Someone to avoid:

ANYONE WHO LEAVES A MESSAGE

All messages in a Murder Village are bad news. It means someone Knows Something. Don’t leave messages. Don’t hang around people who do.

At the Manor, beware of “THE FOLLY”:

It’s a small, fake temple at the far side of the pond, perfect for picnics, trysts, and casual strangulations.

At “THE SHOOTING PARTY”:

This is supposed to be a fun day out in which some servants shake birds out of the bushes while other servants carry and reload guns, all so that the aristocracy can shoot at anything with wings. The shooting party is like the village fête – this is how the nobles weed one another out right in the open. Always assume someone is roaming the grounds with a shotgun looking for long-lost cousin Hugo who just showed up and got top billing in the will.

Or “THE DINNER PARTY”:

For when you want to be murdered, but you don’t have an entire weekend to spare.

This should give you an idea of the humor included in this informative little book. And who knows? Purchasing a copy may save your life.

maureenjohnsonbooks.com

jaycooperbooks.com

Find this review on Sonderbooks at: www.sonderbooks.com/Nonfiction/your_guide_to_not_getting_murdered.html

Disclosure: I am an Amazon Affiliate, and will earn a small percentage if you order a book on Amazon after clicking through from my site.

Disclaimer: I am a professional librarian, but the views expressed are solely my own, and in no way represent the official views of my employer or of any committee or group of which I am part.

What did you think of this book?