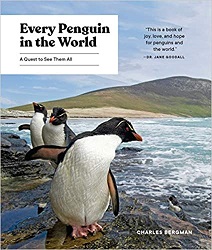

Review of Every Penguin in the World, by Charles Bergman

A Quest to See Them All

by Charles Bergman

Sasquatch Books, 2020. 193 pages.

Review written September 30, 2020, from a library book

Starred Review

I wouldn’t have called myself a penguin lover before reading this book, though I certainly don’t dislike them. Who could? But reading this book has me fully converted.

The author is an English professor. He and his wife decided to take trips to see every current penguin species in the world. And he took wonderful photographs on these journeys.

The photographs do steal the show. Penguin chicks are adorably cute, and adults are sometimes comical, sometimes beautiful, and always striking. Their location in remote southern locations adds to the beauty of these photographs.

And it’s difficult to get to the remote locations where penguins live, so the story of this quest is a story of adventure. The author does a great job of communicating the dangers and difficulties of their travels while also conveying the way the penguins changed his life spiritually and called him to this pilgrimage.

Of course, there’s also information about how so many penguin species are endangered and what we can do to help. If a universally beloved creature is in danger, how can we expect to save creatures that aren’t so adorable? So this book is also a wake-up call.

I found myself looking at the photos here over and over again, but the words drew me in as well. This is a wonderful little book that you can be sure you’ll want to come back to. I think I’m going to order my own copy to be able to look at pictures of penguins whenever I want to be uplifted.

Find this review on Sonderbooks at: www.sonderbooks.com/Nonfiction/every_penguin_in_the_world.html

Disclosure: I am an Amazon Affiliate, and will earn a small percentage if you order a book on Amazon after clicking through from my site.

Disclaimer: I am a professional librarian, but the views expressed are solely my own, and in no way represent the official views of my employer or of any committee or group of which I am part.

What did you think of this book?