It’s Sonderling Sunday! That time of the week when I play with language by looking at the German translation of children’s books or, in this case, English translations of German fairy tales.

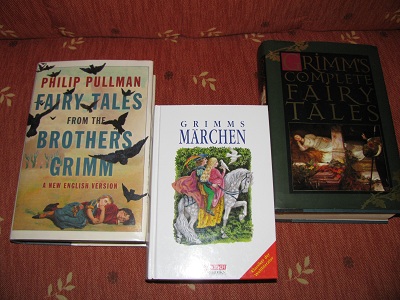

This is the week I normally would have gone back to James Kennedy’s Der Orden der Seltsamen Sonderlinge, but it so happens that my hold just came in on Philip Pullman’s Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version. I know, I know: I should purchase my own copy. I probably will. But I want to see how its different from the nice edition I already have, which was given to me in Germany by Jeff Conner, the librarian who first hired me to work in a library. So for now, I’ll use Philip Pullman’s book for the couple weeks I have it checked out.

Now, Philip Pullman says in the introduction, “A fairy tale is not a text.” So I’m curious what elements of his own he has put into these fairy tales….

I’m going to use the edition of Grimm’s Märchen I purchased in Germany, not necessarily based on “the seventh edition of 1857” that Philip Pullman worked from. I’m going to look at his translation, along with the Barnes & Noble English edition I already have, copyright 1993, which doesn’t identify the translator.

Let’s start with “Der Froschkönig oder der Eiserne Heinrich,” which Philip Pullman correctly translates as “The Frog King or Iron Heinrich” rather than calling it what we’re used to in English, “The Frog Prince.”

Right away, I’ve got a discrepancy with my German version. It starts immediately with the princess, eine Königstochter. However, both English versions give more of a setting:

Barnes & Noble: “Long ago, when wishes often came true, there lived a King whose daughters were all handsome, but the youngest was so beautiful that the sun himself, who has seen everything, was bemused every time he shone over her because of her beauty. Near the royal castle there was a great dark wood, and in the wood under an old linden tree was a well; and when the day was hot, the King’s daughter used to go forth into the wood and sit by the brink of the cool well.”

That’s where my German version starts: Es war einmal eine Königstochter, die ging hinaus in den Wald und setzte sich an einen kühlen Brunnen.

(“There was once a king’s daughter, who went out in the Wood and sat by a cool well.”)

Pullman begins like this: “In the olden days, when wishing still worked, there lived a king whose daughters were all beautiful; but the youngest daughter was so lovely that even the sun, who has seen many things, was struck with wonder every time he shone on her face. Not far away from the king’s palace there was a deep dark forest, and under a lime tree in the forest there was a well. In the heat of the day the princess used to go into the forest and sit by the edge of the well, from which a marvellous coolness seemed to flow.”

So my immediate conclusion: They’re both using a different German edition than what I have. But it does continue on as mine does.

I like this expression:

rollte und rollte geradewegs in das Wasser hinein (“rolled and rolled directly into the water”)

B&N: “rolled in”

Pullman: “ran right over the edge and disappeared”

Oh those yammering whiners!

Da fing sie jämmerlich zu weinen an und zu klagen

B&N: “Then she began to weep, and she wept and wept as if she could never be comforted”

Pullman: “She began to cry, and she cried louder and louder, inconsolably.”

Königstochter, was jammerst Du so erbärmlich?

(“King’s daughter, what makes you cry so pitifully?”)

B&N: “What ails you, King’s daughter? Your tears would melt a heart of stone.”

Pullman: “What’s the matter, princess? You’re crying so bitterly, you’d move a stone to pity.”

Du garstiger Frosch (“you nasty frog”)

B&N: “Oh, is it you, old waddler?”

Pullman: “Oh, it’s you, you old splasher.”

Gesellen

both English: “companion”

Deinem goldenen Tellerchen (“your little gold plate”)

B&N: “your plate”

Pullman: “your dish”

Was schwätzt dieser einfältige Frosch wohl

(“Whatever this stupid frog babbles…”)

B&N: “What nonsense he talks!”

Pullman: “What is this stupid frog saying?”

Maul

both: “mouth”

Am anderen Tage sa? die Königstochter an der Tafel, da hörte sie etwas die Marmortreppe heraufkommen, plitsch, platsch, plitsch, platsch!

B&N: “The next day, when the King’s daughter was sitting at table… there came something pitter-patter up the marble stairs”

Pullman: “Next day the princess was sitting at table… when something came hopping up the marble steps: plip, plop, plip, plop.”

(Props to Pullman for plip, plops!)

wie ihr das Herz klopfte

B&N: “how quickly her heart was beating”

Pullman: “that her heart was pounding”

Okay, next there’s poetry. I do like Pullman’s better.

Königstochter, jüngste

mach mir auf,

wei?t Du nicht was gestern

Du zu mir gesagt

bei dem kühlen Brunnenwasser?

Königstochter, jüngste,

mach mir auf.

(Literally: “King’s daughter, youngest

let me out,

do you know what yesterday

you said to me

by the cool well water?

King’s daughter, youngest

let me out.”)

B&N: “Youngest King’s daughter,

Open to me!

By the well water

What promised you me?

Youngest King’s daughter

Now open to me!”

Pullman: “Princess, princess, youngest daughter,

Open up and let me in!

Or else your promise by the water

Isn’t worth a rusty pin,

Keep your promise, royal daughter,

Open up and let me in!”

(Much nicer poetry, don’t you agree?)

I always like this German word:

hüpfte herein

both: “hopped in”

erschrak

B&N: “was afraid”

Pullman: “frightened”

I don’t find this exact line in the English versions, but I like it:

sie war bitterböse in ihrem Herzen (“She was bitter-evil in her heart”)

Sie packte der Frosch mit zwei Fingern (“She grabbed the frog with two fingers”)

B&N: “She picked up the frog with her finger and thumb”

Pullman: “She picked the frog up between finger and thumb”

warf die ihn bratsch! an die Wand

(literally: “threw him Bratsch! on the wall”)

B&N: “she threw him with all her strength against the wall”

Pullman: “threw him against the wall” (Shucks, no sound effects!)

I love it! My B&N English version goes straight to the wedding. In German, it says, Der war nun ihr lieber Geselle, und sie hielt ihn wert wie sie es versprochen hatte, und sie schliefen vergnügt zusammen ein.

(Literally: “He was now her beloved companion, and she held him dear as she had promised, and she slept together with him with pleasure.”)

Pullman is more coy: “And she loved him and accepted him as her companion, just as the king would have wished.” [Yeah, I bet the king would have wished it!] “…Then they fell asleep side by side.”

kam ein prächtiger Wagen mit acht Pferden bespannt, mit Federn geputzt und goldschimmernd

B&N: “there came to the door a carriage drawn by eight white horses, with white plumes on their heads, and with golden harness”

Pullman: “It was pulled by eight horses with ostrich plumes nodding on their heads and golden chains shining among their harness.”

treue Heinrich

B&N: “faithful Henry”

Pullman: “Faithful Heinrich”

nicht vor Traurigkeit zerspringe

literally: “not from sadness shatter” (“spring apart”)

B&N: “to keep it from breaking with trouble”

Pullman: “to stop it bursting with grief”

It finishes up with a poem, which this time Pullman translates as prose.

Heinrich, der Wagen bricht!

Nein, Herr, der Wagen nicht,

es ist ein Band von menem Herzen,

das da lag in gro?en Schmerzen,

als Ihr in dem Brunnen sa?t,

als Ihr ein Frosch wart.

Literally: “Heinrich, the carriage breaks!

No, my lord, not the carriage,

it is the band around my heart,

that was in great pain,

when you sat in the well,

when you were a frog.”

B&N: “The wheel does not break,

‘Tis the band round my heart

That, to lessen its ache,

When I grieved for your sake,

I bound round my heart.”

Pullman: “‘Heinrich, the coach is breaking!’

‘No, no, my lord, it’s just my heart. When you were living in the well, when you were a frog, I suffered such great pain that I bound my heart with iron bands to stop it breaking, for iron is stronger than grief.”

Pullman includes a comment about Faithful Heinrich in his notes at the end of the story:

The figure of Iron Heinrich appears at the end of the tale out of nowhere, and has so little connection with the rest of it that he is nearly always forgotten, although he must have been thought important enough to share the title. His iron bands are so striking an image that they almost deserve a story to themselves.

So, verdict? Undecided. It’s a little frustrating that I’m obviously not using the same German text as both of the English translators. The B&N translator leans a little more literal with what I do have, and Philip Pullman, no surprise, uses more beautiful English, while seeming to retain the points made in the story.

This isn’t as fun to play with as James Kennedy’s ever-interesting phrases to translate, since fairy tales almost by definition use simple language. But it’s still fun to look at these classic tales.

Was schwätzt dieser einfältige Frosch wohl, I still think it’s fun to hear a classic story told in different ways — and different languages.