Last Friday night, I got to attend the reception for the Printz Award and Honor winners. One thing I like about this reception is that all the winners give a speech – not the big winner only. Here are my notes from their speeches:

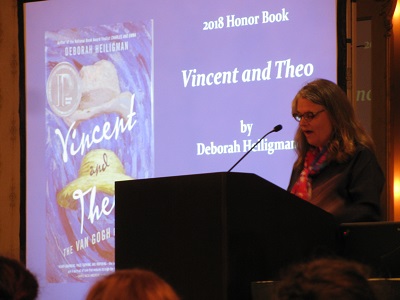

Deborah Heiligman, for Vincent and Theo:

Deborah Heiligman doesn’t remember receiving the Printz call. “Apparently, I screamed.” She told us the story of getting Transient Global Amnesia. She started asking “What just happened? What’s going on?” She was agitated and confused. She could only remember for 90 seconds at a time. This is why she missed the YALSA Nonfiction Awards in Denver.

It turns out that TGA can be caused by strong emotion. Is the moral to “try not to get too excited”?

Vincent painted for art’s sake – and Theo’s approval.

Vincent was a great artist in spite of his mental illness.

We want to leave the world a souvenir. Wake someone up to the world.

Laini Taylor, for Strange the Dreamer:

She works hard at not getting hopes up at award time. It’s a unique form of meditation – “No hope.”

But Hope isn’t something you decide not to have. Hope is all surly and defiant.

Usually good news comes in pieces, over time, with assembly required.

When she did get the call, there was a “totally overwhelming clobber of emotion.”

“Sometimes this writing thing feels like launching a paper boat when you can’t see the far shore.”

With Fantasy, recognition feels extra good, since Fantasy is often dismissed.

Shame is heavy — but it is a safeguard. It says decency is real and lines exist. Our government is being shameless and erasing lines. The thought of her 8-year-old daughter being separated from her makes her lose her mind.

As readers and writers, we imagine other lives. “Decency depends on empathy. Empathy depends on imagination.”

Strange the Dreamer hinges on whether it’s possible to save a traumatized child from her consuming hatred. As long as there’s even one dreamer left — there’s hope.

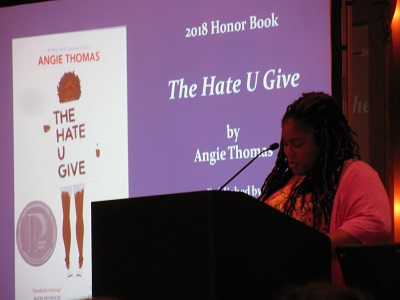

Angie Thomas, for The Hate U Give:

This past week has been trying as horrific events unfold in our nation. She can revive her characters with the stroke of a pen, but she can’t revive Antwone Rose, who was gunned down this week in Pittsburgh.

In fiction, she can delete injustice.

We should not live in a world where children become activists. Kids shouldn’t have to tell us we need to change.

These young people feel fired. “The least I can do is fan the flames.”

What children’s literature has always shown is that anyone can be a superhero. Yes, even you.

Let’s not leave the work all on them. Acknowledge the injustice around you to the point it angers and exhausts you.

“By faith, I thank you for changing the world.”

Jason Reynolds, for Long Way Down:

There are good writers and good storytellers, not so many people are both.

He wants people to read his books more than once.

He’s proud to win a Printz Honor, especially since the first Printz winner was Walter Dean Myers.

This book was a passion project. Based on when he was a 19-year-old college kid in 2003. His mom was engulfed in the flames of cancer. A friend called and told him that their friend had been murdered.

He remembers the blade of grief. He remembers the anguish of their friend’s mother. All his friends are missing parts of themselves – like cancer. The death changed them chemically. They realized they could do what they couldn’t do before – they could kill.

This book is about the weight of anger, or the rules, but also the weight of cages, the weight of separation, the weight of us.

What happens in the end? “I don’t know.”

The fate of a child is in your hands.

Now we’re certain his friend’s legacy will live on forever.

Nina LaCour, for Award winner We Are Okay:

This is the first time an Own Voices book about queer girls has won the Printz.

We Are Okay is the product of a painful time.

Her own grandfather died when she was hospitalized with preeclampsia. She had a vision of him pushing her on a swing and with his arms open wide in greeting. He grew up in New Orleans.

Gramps in the novel is an altogether different man.

Since orphans are a trope in children’s literature, for her first few books, she did her best to keep the parents alive.

Grief orphans us.

Her own parents split soon after her baby was born, and it was as if her own past were erased.

The big question of the book: When we don’t recognize our own past, what can anchor us?