I like to post highlights from ALA Annual Conference each year that I attend. It’s all so overwhelming when it happens, and writing up notes helps me absorb what I learned and what I experienced. You can follow these posts in the Conference Corner category. It’s already been a couple of weeks since I was finally at an in-person conference again. It was in Washington, D.C., the same as the last time it was in-person. I still don’t feel great about traveling in an airplane, but this meant I could drive in and out of the city each day.

The first day of the conference was Friday, June 24, 2022. I got there early in the afternoon to get my badge, show my vaccination status, and show my doctor’s note to get permission to bring a wheeled bag onto the exhibit floor.

My first activity was a fun excursion — ALSC (the Association for Library Services to Children) was sponsoring members to visit Planet Word — a new museum of the spoken word — a few blocks away from the convention center. Unfortunately, I remembered the time wrong and got there before the main group of people. I had fun exploring the museum — it’s worth a trip — but unfortunately my mind was on the conference so I didn’t linger enough to really do it justice.

I went back to the conference in time for the Opening Session with ALA president Patty Wong interviewing the chairperson of the FCC, Jessica Rosen Worcel. They mainly discussed efforts to get broadband to the underserved, with the help of libraries — and how much difference this makes in people’s lives.

She talked about an “Emergency Connectivity Fund” to use to help schools and libraries give students and patrons internet connectivity, a continuation of the eRate program that began in 1996, “a quiet powerhouse.” They’ve made eRate easier to apply for.

Kids who don’t have connectivity fall behind. And here she mentioned my friend Alma, who works in a rural school library, and the kids need internet access to do their homework.

Kids are affected by the digital divide even more after the pandemic. We can’t stop until every student has access at home.

The FCC has signed a Memo of Understanding with IMLS to work with libraries to connect communities.

After the Opening Session, the Exhibits opened. I showed a lot of restraint and only picked up nine books, some of them signed. I lost that restraint the next day, but it was a good start!

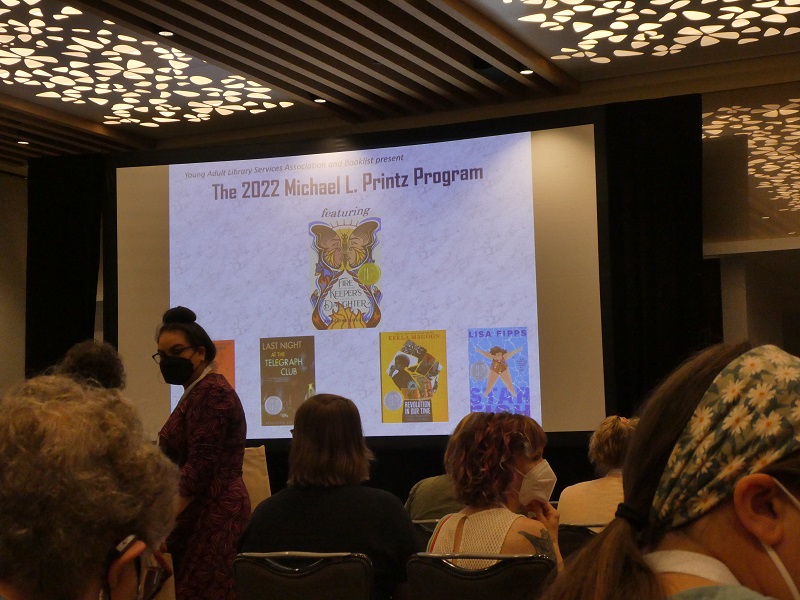

Then I dropped the books in my car and found a hotel bathroom where I could change my clothes to go to the 2022 Michael L. Printz Awards.

I love that at the Printz Awards, the winner and all the honor authors speak, instead of just the winners. Here are some notes from those speeches, with the honor authors first:

Angie Thomas, author of Concrete Rose

First, she broke to us that her book being set in 1998-1999 makes it “Historical.” Back in the day when women had full rights.

Black men didn’t have cell phones with cameras to document police brutality.

Life should be different by now. What are we doing to change things in 2040?

Limited perspectives create limited leaders. We are frontline soldiers in the battle against censorship.

The real Mavericks are invisible until they’re a threat. Acknowledge the roses. Fight for them. Help them grow.

Andrew Carr (editor), reading the speech for Malinda Lo, author of Last Night at the Telegraph Club

(He was really cute reading the nice things she said about her editor!)

Book bans have skyrocketed and laws targeting librarians. Those who seek to repress the new reality — they have teamwork. We need teamwork, too.

Librarians curate books about all of us for all of us. We have a team behind us, too.

All the authors are on our team. Our team is bigger than their team.

Our team is better, motivated by truth, curiosity, and compassion.

You are not alone!

Kekla Magoon, author of Revolution in Our Time: The Black Panther Party’s Promise to the People

20 years ago, she thought of the Black Panther party as Black guys with guns — so scary, we didn’t talk about it.

The first thing that caught her attention was when she found out about the free breakfast program. She became eager to learn more. She was angry it had been kept from her.

This was the project of her passion. She spent 10 years on study and travel and gathered nearly 180 photos.

Meanwhile, echoes rang out constantly.

After all that wait, this is the right book at the right time.

The struggle for representation continues. Black history is our history. We need multiple perspectives.

We have to trust our kids to build a better future.

Lisa Fipps, author of Starfish

Librarians have to fight a lot. Thanks for all of it!

It’s unknown how many lives have been saved by school librarians welcoming loners at lunch.

For many children and for her, Starfish is nonfiction and biography.

Children need this book.

Fat children have a right to take up space.

To children: I’m sorry. People hurt you, and then laugh.

Words can hurt, and words can also heal. Words can set us free.

Angeline Boulley, author of Firekeeper’s Daughter

Her Ojibwe language and culture are still here — because of stories.

We’re honoring stories and storytellers. She really is a Firekeeper’s daughter. Only good thoughts and words are allowed around a ceremonial fire. Stories are good medicine.

She told about the “creative jigsaw puzzle” behind the story that is her book.

She was 18 before she read a book with an indigenous protagonist. It was disappointing, and it was also too late.

Representation in children’s books matters.

She mentioned the “windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors” we talk about in children’s books and quoted Debbie Reese — “Some of those windows need curtains.”

She writes to preserve her culture and edits to protect it.

There are traumatic events in her book, but it’s not a tragedy.

Stories are good medicine. They are like women: Strong like the tide, with forces too powerful to control.