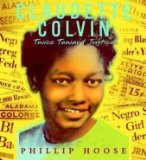

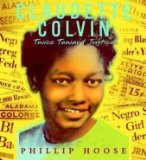

Claudette Colvin

Claudette Colvin

Twice Toward Justice

by Philip Hoose

Melanie Kroupa Books (Farrar Straus Giroux), New York, 2009. 133 pages.

2009 National Book Award Winner

2010 Newbery Honor Book

2010 Sibert Honor Book

2010 YALSA Excellence in Nonfiction Honor Book

Starred Review

Sonderbooks Stand-out 2010: #1 Children’s Nonfiction

I always thought that Rosa Parks was the first black woman to refuse to give up her seat on segregated buses in Montgomery, Alabama. However, nine months earlier, a high school junior named Claudette Colvin “had been arrested, dragged backwards off the bus by police, handcuffed, and jailed for refusing to surrender her bus seat to a white passenger.”

Philip Hoose did extensive research, and had many interviews with Claudette Colvin herself. Here she describes what it was like:

“One of them said to the driver in a very angry tone, ‘Who is it?’ The motorman pointed at me. I heard him say, ‘That’s nothing new . . . I’ve had trouble with that “thing” before.’ He called me a ‘thing.’ They came to me and stood over me and one said, ‘Aren’t you going to get up?’ I said, ‘No, sir.’ He shouted ‘Get up’ again. I started crying, but I felt even more defiant. I kept saying over and over, in my high-pitched voice, ‘It’s my constitutional right to sit here as much as that lady. I paid my fare, it’s my constitutional right!’ I knew I was talking back to a white policeman, but I had had enough.

“One cop grabbed one of my hands and his partner grabbed the other and they pulled me straight up out of my seat. My books went flying everywhere. I went limp as a baby — I was too smart to fight back. They started dragging me backwards off the bus. One of them kicked me. I might have scratched one of them because I had long nails, but I sure didn’t fight back. I kept screaming over and over, ‘It’s my constitutional right!’ I wasn’t shouting anything profance — I never swore, not then, not ever. I was shouting out my rights.

“It just killed me to leave the bus. I hated to give that white woman my seat when so many black people were standing. I was crying hard. The cops put me in the back of a police car and shut the door. They stood outside and talked to each other for a minute, and then one came back and told me to stick my hands out the open window. He handcuffed me and then pulled the door open and jumped in the backseat with me. I put my knees together and crossed my hands over my lap and started praying.”

After the incident, reactions were mixed:

“Opinion at Booker T. Washington was sharply divided between those who admired Claudette’s courage and those who thought she got what she deserved for making things harder for everyone. Some said it was about time someone stood up. Others told her that if she didn’t like the way things were in the South, she should go up North. Still others couldn’t make up their minds: no one they knew had ever done anything like this before.

“‘A few of the teachers like Miss Nesbitt embraced me,’ Claudette recalls. ‘They kept saying, “You were so brave.” But other teachers seemed uncomfortable. Some parents seemed uncomfortable, too. I think they knew they should have done what I did long before. They were embarrassed that it took a teenager to do it.'”

After Claudette was convicted of violating the segregation law, disturbing the peace, and ‘assaulting’ the policemen, things got even worse. She says,

“Now I was a criminal. Now I would have a police record whenever I went to get a job, or when I tried to go to college. Yes, I was free on probation, but I would have to watch my step everywhere I went for at least a year. Anyone who didn’t like me could get me in trouble. On top of that I hadn’t done anything wrong. Not everyone knew the bus rule that said they couldn’t make you get up and stand if there was no seat available for you to go to — but I did. When the driver told me to go back, there was no other seat. I hadn’t broken the law. And assaulting a police officer? I probably wouldn’t have lived for very long if I had assaulted those officers.

“When I got back to school, more and more students seemed to turn against me. Everywhere I went people pointed at me and whispered. Some kids would snicker when they saw me coming down the hall. ‘It’s my constitutional right! It’s my constitutional right!’ I had taken a stand for my people. I had stood up for our rights. I hadn’t expected to become a hero, but I sure didn’t expect this.

“I cried a lot, and people saw me cry. They kept saying I was ’emotional.’ Well, who wouldn’t be emotional after something like that? Tell me, who wouldn’t cry?”

Not long after, Claudette met an older man who seemed to be a friend, but took advantage of her vulnerability. She got pregnant out of wedlock. So she wasn’t seen as a suitable role model for the movement to stop segregation. Seven months later, another teenager, Mary Louise Smith was also arrested for refusing to give up her seat, but she, too, was not seen as someone who could serve as the public face of a mass bus protest.

Eventually, they did find a suitable person in Rosa Parks. The bus boycott started. The boycott did not end until the case Browder vs. Gale, where four black women sued the city of Montgomery and the state of Alabama, saying that bus segregation was unconstitutional. One of those plaintiffs in the suit was Claudette Colvin, and her testimony was key in getting a positive verdict. Not until the verdict was upheld in the Supreme Court did the segregation on the buses end.

This book was especially good to read after reading The Help, by Kathryn Stockett, since it also dealt with race relations in the South at that time. Philip Hoose researched the events so well, and presents clearly all the drama of the situation, along with the emotions of the people involved. How wonderful that people can finally hear the story of a teenage girl who stood up — no, sat down — for what’s right.

Buy from Amazon.com

Find this review on Sonderbooks at: www.sonderbooks.com/Childrens_Nonfiction/claudette_colvin.html

Disclosure: I am an Amazon Affiliate, and will earn a small percentage if you order a book on Amazon after clicking through from my site.