Continuing my coverage of my wonderful time at the 2013 ALA Annual Conference in Chicago, last Friday I was at the ALSC’s preconference, in honor of the 75th anniversary of the Caldecott Medal. Even though I don’t consider myself an art expert by any means (I’ve always dreamed of being on the Newbery committee, but never the Caldecott), when I heard the event was taking place at the Art Institute of Chicago, I couldn’t resist.

One of the wonderful things about the preconference? Being with a large group of people who take picture books seriously, discuss them as art, and believe in the magic of what they do for children.

I was happy that I’m getting to know more and more members of ALSC (the Association for Library Service to Children). I saw many people that I have already met at the breakfast, and met some new people. Capitol Choices, a group from the DC area that I attend, was well-represented.

The first speaker was Brian Selznick, who put on the sparkly jacket he wore for the Caldecott Banquet.

After taking this picture, I realized it was rather futile to take pictures of every speaker! Oh well.

Brian gave an illustrated talk about the history of the Caldecott Medal. He talked about how Randolph Caldecott and Frederick Melcher were about entertaining books just for children. Caldecott’s pictures added to his books; they weren’t just repeating the words. The pictures had a sense of life, rooted in his sense of humor. And that sense of humor was a shield against tragedy.

Brian also talked about Maurice Sendak, their friendship, and how Where the Wild Things Are sums up what the Caldecott is all about. It shows how Max went farther than he intended and came home safe again. It scared adults. It contained life.

The second session was a Spotlight with Erin and Philip Stead and their editor, Neal Porter. The title was “Matching Words and Pictures,” but they gave it the alternate title: “Everyone Makes Mistakes.” I liked the way they showed some early versions of their work and how their editor helped them to the final product.

One interesting point they made: When they eliminated excess words, they actually slow readers down. Sometimes when there are too many words on a page, readers don’t spend as much time looking at the pictures.

With And Then It’s Spring, Erin wanted people to pay attention. She wanted to “trap readers with pictures.”

The next session was with Chris Raschka and his editor, Lee Wade, looking at the making of A Ball for Daisy. A Ball for Daisy is wordless, so you might not think it needs a lot of editing? You’d be wrong. Chris Raschka gave the alternate title: “The Daisy Journey: Not a Walk in the Park.” The book went through multiple versions, even multiple styles. He joked, “Should the ball die? All these questions.”

I was simply amazed at how far the book came from his original sketches to the practically perfect picture book that won the Caldecott Medal last year. A fascinating look at the process that got it there, a give and take between artist and editor.

After that was lunchtime, and they kept us engaged with an Honor Book panel — artists who had won Caldecott honors.

That’s Leonard Marcus moderating, followed by Kadir Nelson, Melissa Sweet, Pam Zagarenski (hidden, sorry), and Peter Brown.

Here’s a shot that includes the lovely room we were in, the former Trading Floor:

Leonard Marcus asked some intriguing questions, starting off with “Why picture books?”

Kadir Nelson: “Books chose me. I always was a storytelling artist.”

Melissa Sweet: She saw Little Bear and felt she had come home. It is like a mini-movie. Art is so varied, she’ll never get bored.

Pam Zagarenski: She’s always been illustrating. Even as a girl, she wanted to be Beatrix Potter when she grew up. She’s never had any other ambition. What she had to do.

Peter Brown: He was a reluctant reader, and more interested in creating than reading. He thought he’d be an animator, but hated it because he wanted to tell his own story.

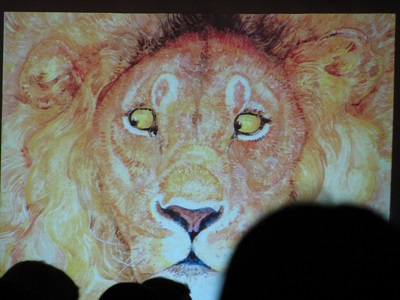

There was more intriguing talk about making art and making picture books, and then we got to hear from Jerry Pinkney and his editor, talking about The Lion and the Mouse. Sorry that my picture of them is blurred:

He talked about his own history, what got him into picture books. He used to sneak down where he could watch a printing press in action. He enjoys the rhythm… of the printing press, of turning the page.

With The Lion and the Mouse, the editorial, design, and production all worked together. What it’s about is holding that object in your hands.

They also showed the book set to music, with pictures inserted from Jerry’s first book about Anansi the Spider. He said, “I’d love my art to feel the way music sounds.”

After those inspiring sessions, we had an elective. I wish I could have gone to all of them! I chose Leonard Marcus’s talk on Randolph Caldecott. (Oh, and I met Eric Carpenter, a fellow frequent Heavy Medal commenter!)

Leonard’s coming out with a book about Randolph Caldecott. (I wish I had gotten to his signing the next day, but had something else going on.) He titled the talk, “Randolph Caldecott: The Man Who Could Not Stop Drawing.”

Randolph Caldecott was not a sentimentalist. Even though he made books for children, he wrote about the adult world. (He showed us some humorous examples.) Leonard showed us slides of places from Caldecott’s life. His father was an accountant and had lots of practical ideas for Randolph. When he worked in a bank, he discovered that bank slips are great for drawing on. (And we saw some pictures of those slips.)

Picture books for fun were a new idea in Caldecott’s time. It was also a time of the explosion of train travel, so they sold books for people to take on trains. Color printing was new, and they developed the predecessors to the motion picture.

Some hodgepodge notes from this talk: Caldecott was thinking of how to pare down a picture book to the fewest possible lines. When he traveled on trains he’d make “lightning” sketches. He played with composition in new ways. He only once did a book with animals in human dress, and you can see its influence on Beatrix Potter, who admired Randolph Caldecott with a “jealous appreciation.” He invented all the tricks of the trade.

The final general session was Paul O. Zelinsky speaking on “The Caldecott Medal in the 21st Century.”

He wore his Rapunzel tie, which he painted just after turning in the artwork for his Caldecott-winning book Rapunzel

He did some joking about what might happen with the Caldecott in the future. (“We can extrapolate. They’ll all go to Jon Klassen.”) But he did point out that we can’t figure out what will happen.

“Picture books may change, but Story never will.”

He pointed out that your consciousness *is* story — the autobiographical self.

“We are stories. So we cling to stories.”

“Stories take you out of yourself and take you away.”

He talked about writing Rumpelstiltskin and how he got pictures of straw from the New York Public Library photographic archive. He wanted to find a spinning wheel, but there was none to be found anywhere in New York City. (I loved his aside: It was just like the situation in Sleeping Beauty. Made him wonder.)

He concluded that the picture books of the future and those that get honored are completely unpredictable. But bottom line, speaking to that crowd of librarians, “The Caldecott of the future is up to you.”

By the time I finished that amazing Preconference, the entire weekend in Chicago was already worth it. I was energized and inspired and all the more excited about showing children the wonder of art and words and story that picture books are.