KidLitCon in New York City! At the New York Public Library! KidLitCon is a conference for bloggers who blog about children’s books. I went to KidLitCon09 close to home in DC, to KidLitCon11 in Seattle, and just had to go when it was so close by and free to boot.

I’m way behind on my Conference Corner posts. So, for fear I’ll never get to KidLitCon, I decided to post the same night I got back, when everything’s fresh. Instead of giving you all my notes, I’m just going to give you the high points. Here are the things I took home from KidLitCon12, in chronological order.

1. Publisher Previews are Dangerous.

I only was able to go to one preview, since I flew in to New York at noon, and that was probably a good thing. It was at the offices of HarperCollins going over books they’re publishing soon.

Why are previews dangerous? First, I had packed lightly. They gave us a full bag of advance reader copies, as well as three hardbound published books and a blank book. Did I tell them, no, I couldn’t possibly carry the bag home on the plane or fit it in my suitcase? No, I did not. Did I even tell them my neurologist said, since my vertebral artery dissection, that it’s not a good idea for me to walk around carrying more than 15 pounds? No, I did not.

Now, don’t worry, as I walked 20 blocks up 5th Avenue to our dinner (which I actually enjoyed. Definitely gave me the feel of New York City.), I found a FedEx and stuck the bag on their counter, and had them ship the whole bag home to me. But the other reason the preview was dangerous is after hearing them talk about the upcoming books, I want to read every single book! Was I hurting for ideas of books to read? No, I was not. Did I need to know about more books I’d like to read? No, I did not. Does that make me want to read them any less? No, it does not.

Now, later in the conference, I did end up with two more hardbound and two more paperback books. My suitcase ended up being hard to close, but I managed it. But to show how dangerous I find publisher previews, and how impossible I find it to resist free books — this morning I woke up from a dream where I was in a line to get advance reader copies of some adult books I didn’t even find very interesting, and which I knew I wouldn’t be able to fit in my suitcase, and when I knew it was Sunday and I wouldn’t be able to ship them — but I took them anyway! I was so relieved when I woke up! I had not taken more books than I could carry after all.

Yeah, I have a problem.

2. KidLit Bloggers are My People.

Okay, I knew this already. But it was a lovely to spend a weekend with other people who are a little nuts about children’s books. My resolution: Read more of their blogs! More regularly! These are my people, and it was wonderful to see the ones I already knew and meet some I hadn’t met before.

And I got to be roommates again with Lisa Song, who blogs at Reads for Keeps. She helped me navigate the subways, and having some quieter time with her between busy days was definitely a highlight of the conference.

3. Grace Lin shines with niceness and has a Really Cute Baby.

4. Sushi tastes good.

Who would have thought?

5. You should be creating something you want to share with the world, not something to show how clever or talented you are.

This was from Grace Lin’s talk. Just an inspiring reminder why I blog: To share special books with other people.

6. Although they are My People, not all Children’s Book Lovers are introverts like me. The extroverted ones are really fun to be around, though.

Here’s Pam Coughlan, Mother Reader, “auctioning” off ARCs from the Publisher Previews the day before. (I managed not to take any, I’m proud to say.) That’s Charlotte, middle grade science fiction and fantasy specialist, on the right. (Who is in the middle?)

7. Make your blog easy to share.

Resolution: Add more sharing buttons, besides the Tweet button. Must get around to this….

8. “If you talk like you’re alone in a room, you will be.” — Marsha Lerner

This point brought a small epiphany for me. Since I began Sonderbooks as an e-mail newsletter consisting of book reviews, I think of it as my thoughts I’m sharing with people. I’m talking like I did when I was the instructor lecturing the classroom.

9. Ask questions you want answers to.

All these last three points are from Marsha’s talk. And, mulling them over, I had an idea this morning. I think I am going to start using comments to discuss the books I review with other people who have read them. So I will put Spoilers in the comments. So far, I don’t get a lot of comments on book reviews. I mean, what do you say if you haven’t read the book? You can say, I’m looking forward to reading that. But wouldn’t it be nice to be able to talk about that annoying or brilliant thing at the end of the book and find out what other people think? I could use the comments for deeper discussion.

What do you think? I am honestly curious. Do you think spoilers in the comments is a good idea, if I put lots of warnings? My main blog doesn’t show comments, and on my website, you’d have to click over to the blog to see them, and I’d make sure to put warnings. Do you think it will work?

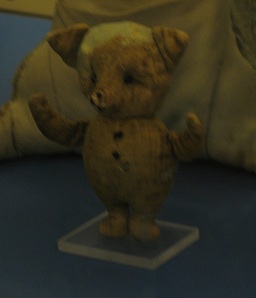

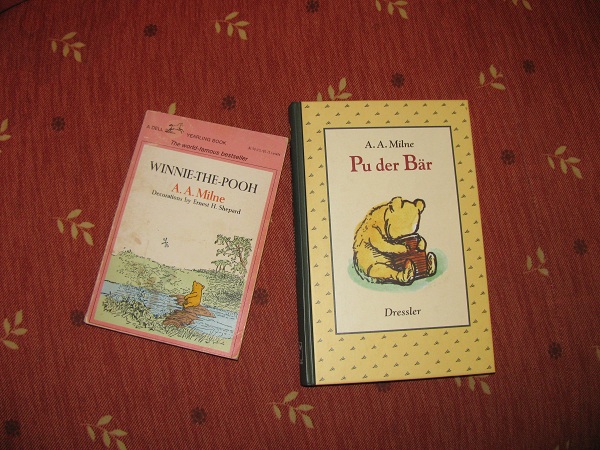

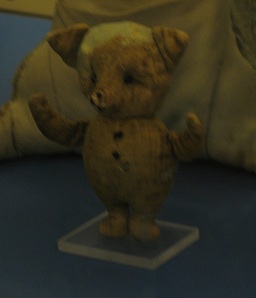

10. Winnie-the-Pooh!!!!! The Original!!!!

Okay, this was NOT something I took home with me, but this WAS a big huge enormous thrill. I got to see the original animals that Christopher Robin played with! Don’t they look so much like the Ernest Shepard illustrations? Especially Tigger:

And you can clearly see why Piglet is truly a Very Small Animal:

Eeyore actually looks patched, which easily explains the story of him losing his tail. All the animals, including dear Pooh, were clearly much loved.

But wait. You may be asking, like me, “What is that OTHER stuffed animal doing in the case?” That, dear reader, is a Travesty. You see, not only was a sequel to Winnie-the-Pooh and The House of Pooh Corner “authorized,” a new character was created. A stuffed animal of this new character was created, and someone had the Very Bad Idea of putting the new stuffed animal in the case with the original toys with whom Christopher Robin once played. Here is a picture Leaving It Out:

I took these pictures on my lunch break, and was so glad I’d made the pilgrimage. Wow.

11. Keep my inner fangirl in check. Maybe?

There was quite a lot of talk about the relationship between writers and bloggers. Do we get too nice because we don’t want to hurt the authors’ feelings? Is our professionalism hurt when we “know” the writer online or have met them in person?

I began writing Sonderbooks when I was working in a library, but was not yet a librarian. Now I’m a librarian, and I’ve been to the William Morris Seminar, and I closely follow the Heavy Medal blog — and I would so love to be on the Newbery committee some day. If I don’t want my reviews to be merely cheerleading, I should practice thinking critically. Yes, I feel I can continue with my policy of only reviewing books I like, but why do I like them? And, come on, it’s more professional if I try not to Squee too hard when I meet an author. Maybe less pictures with them? (And you’ll notice at least I posted Grace only with her baby.) Hmm. I’ll have to work on this one.

12. If you’re doing a PowerPoint presentation, make sure you are not scheduled after Brian Selznick.

This point is courtesy of Maureen Johnson; it seems very wise.

13. Always feel free to bring a friend.

Maureen roped her friend Robin Wasserman into sharing the keynote, and that added lots of fun to the talk.

14. Keep in mind every day why you’re doing what you’re doing.

Another one from Maureen Johnson.

15. Central Park is lovely.

Who knew?

I had a late afternoon flight, so I went into Central Park, and when I walked a little way in, I heard and saw an actual waterfall. So lovely.

I liked the juxtaposition of the trees with the skyscrapers.

Then later I came upon a large lake. Walking through Central Park was simply a lovely way to spend a couple hours after an inspiring weekend.

How about you, other KidLit Bloggers? What did you take away from KidLitCon?