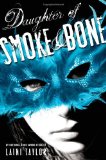

Review of Daughter of Smoke and Bone, by Laini Taylor

by Laini Taylor

Little, Brown and Company, 2011. 420 pages.

Starred Review

This book is incredible. However, I’ll tell you right up front that there was one thing I hated about it: The last three words, those horrible words: “…to be continued.”

Perhaps if I had realized this book was simply Part One, I wouldn’t have minded quite as much. As it was, I was frustrated. The characters are left in quite a fix.

However, if I had known, I might not have rushed to read this, and I’m so glad I did. I will definitely want to reread it when the next book comes out, and to get my hands on the next book just as soon as possible.

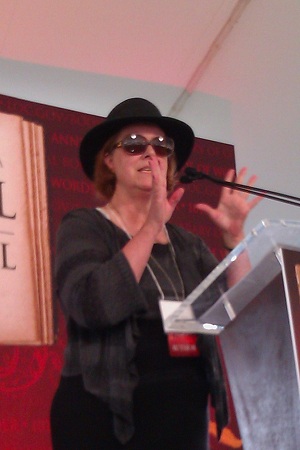

I maintain that Laini Taylor’s imagination is advanced beyond the realm of mere mortals. (In fact, the main character has hair of an unusual color, so perhaps this book is simply autobiographical?) This book creates a world out there, parallel with ours, and it takes the whole book to understand the ins and outs, the ramifications.

Karou is a student living in Prague who’s been brought up by demons. She still does errands for Brimstone, bringing him teeth. She doesn’t know what he uses the teeth for, but he does supply her with small wishes. And plenty of money to purchase the teeth.

Just to let you know, the book begins with frank sexuality. Karou’s ex-boyfriend, whom she caught cheating on her, is not-at-all-subtly trying to win her back. He gets a job posing nude in her life drawing class. Her use of small wishes to get rid of him is a lovely and brilliant example of fitting revenge.

But the rest of the book is much more serious, much more dangerous. Angels are coming to earth and placing black handprints on every door where Brimstone has a portal. Karou gets a rare opportunity to find out more about Brimstone — and he has a very disturbing reaction. She’s cut off from the only family she’s ever known.

And then, why is Karou so powerfully drawn to one particular angel?

But the overarching question, the one it takes the entire book to answer, is the one everyone’s asking her: “Who are you?” Karou doesn’t know the answers herself. When she finds out, it will make all the difference.

This is an incredible book. About love and loyalty and war and life and death. A tale not quite like any other I’ve ever read.

“It wasn’t like in the storybooks. No witches lurked at the crossroads disguised as crones, waiting to reward travelers who shared their bread. Genies didn’t burst from lamps, and talking fish didn’t bargain for their lives. In all the world, there was only one place humans could get wishes: Brimstone’s shop. And there was only one currency he accepted. It wasn’t gold, or riddles, or kindness, or any other fairy-tale nonsense, and no, it wasn’t souls, either. It was weirder than any of that.”

Find this review on Sonderbooks at: www.sonderbooks.com/Teens/daughter_of_smoke_and_bone.html

Disclosure: I am an Amazon Affiliate, and will earn a small percentage if you order a book on Amazon after clicking through from my site.

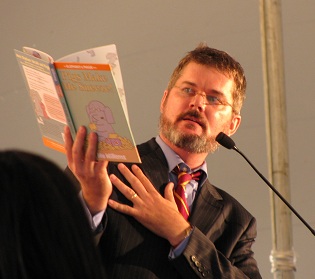

Source: This review is based on an Advance Reader Copy that I got at ALA and had signed by the author.