Review of A Message of Hope from the Angels, by Lorna Byrne

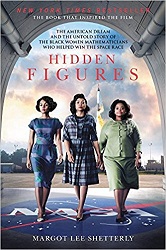

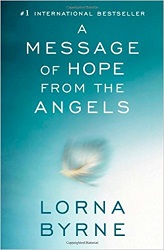

A Message of Hope from the Angels

A Message of Hope from the Angels

by Lorna Byrne

Atria, 2012. 183 pages.

Starred Review

After I read Lorna Byrne’s biography, Angels in My Hair, about how she has been able to see angels all her life, I liked it so much, I ordered two more of her books from Amazon.

This one isn’t autobiographical, but it passes on to the reader things angels have told her. And yes, this book is especially about Hope.

Here’s a section from the first chapter:

Hope brings a community together to make things better, and when it does, I see people get brighter, shine more, and then they can go on to achieve greater things. People who believe things can be changed for the better are beacons of light for us – and need to be supported.

Hope can be given to others. It gives strength and courage, and then hope grows. We all have a part to play in growing hope. In the past, people looked to leaders of churches, communities, businesses, countries to provide a vision of hope for the future, but now many of our leaders are struggling. They are failing to see all the ways in which we can make our world a better place to live.

The angels have told me so much about hope and how much we have to be hopeful about, and have showed me so many different ways in which they help to give us hope.

When I reread that section, I thought, “No wonder this book uplifted me so much!” She covers many different things in this book, but the overall message is that we are loved unconditionally, and there are angels all around us, ready to help.

I’ll quote from a few sections that especially struck me.

One section I liked was where she talked about teacher angels.

Sometimes, on a sunny day, walking through the grounds of the university near where I live, I see students sitting on stone seats opposite the library or sitting on the grass studying, and I see teacher angels with some of them.

Teacher angels always seem to be holding something – a symbol of learning that is relevant to whatever they are teaching. Sometimes they are holding a book or a pointer or a board with writing on it with the words constantly changing. I once saw a bricklayer’s apprentice with a teacher angel who had a trowel in his hand. Teacher angels exhibit the mannerisms we associate with teachers.

I have often seen a teacher angel standing in front of a student, book in hand. The book would look similar to the one the student was working with and seem to be open at the same page. Occasionally I see the teacher angel turn to another page and I smile, knowing that the teacher angel is having difficulty with his student, who is finding it hard to make progress. I have seen teacher angels gently stretch out their hands and touch a student gently on the head with one finger, trying to get the student’s attention. Most of the time this seems to work, but sometimes not. Teacher angels never give up, though, and never lose their patience. I have seen teacher angels blowing on a student’s book and making the page turn, or causing a strong breeze, which blows some of the student’s books and pens onto the ground. That is the teacher angel trying to bring the student’s attention to a particular page or subject, or to simply stop them daydreaming. Teacher angels work very hard to get their students’ attention.

I am always amazed at how few people have teacher angels. After all, all they have to do is ask their guardian angel for help with whatever they are learning and their guardian angel will invite a teacher angel in. In the college I know best, only about one student in ten has a teacher angel with them.

This bit encouraged me in thinking about my many Empty Nester friends:

You can also ask for a teacher angel to help someone else. Just ask your guardian angel for a teacher angel to help the person. Many parents have told me that they have asked for a teacher angel to help their children with their studying – this is so much better than fretting and worrying.

Another special angel she talks about is the Angel of Strength:

When you are exhausted or feeling physically challenged by a task, you can call on the Angel of Strength and ask for his help. He is one angel, but he seems to be able to help many people at the same time. He won’t stay with you, but will come and help you for that particular task where strength is needed.

She concludes the chapter about the various types of help she’s seen angels give with this reflection:

Angels are such a sign of hope. There is always an angel that can help us, regardless of what is going on in our lives. All we have to do is ask. You don’t need to know what angel to ask for; just ask, and your guardian angel will call in the help you need. Isn’t it wonderful to know that there is such an abundance of help there? To me it seems so strange, and sad, that so many people don’t make use of this gift.

I loved the chapter about prayer angels. Here are some sections from it:

I talk and ask the angels to help; I ask the angels to intercede, but I don’t pray to them. I pray only to God. Prayer is direct communication with God.

No one ever prays alone. When you pray to God, there is a multitude of angels of prayer there, praying with you, regardless of your religious faith or how you are behaving. They are there enhancing your prayer, interceding on your behalf and imploring God to grant your prayer. Every time you pray, even if it is only one word, the angels of prayer are like a never-ending stream flowing at tremendous speed to Heaven with your prayers….

I know it’s hard to believe that I see hundreds of thousands of angels of prayer flowing like a river toward Heaven, bringing a person’s prayers and presenting them at the throne of God. But that is what I am shown; it’s as if angels of prayer bring every bit of the prayer – every syllable that is prayed for – up to Heaven. When the person stops praying, the flow stops, but as soon as the person starts to pray again, the stream of angels of prayer resumes.

I loved this part, too:

Every time I go into a church, mosque, synagogue, or temple – or any other holy place – I see hundreds of angels praying, quite aside and separate from any angel of prayer. It doesn’t matter what religion the place belongs to – if any. Whether it’s a building or a space outside, even if the place is no longer being used for prayer, it is still a holy place, and there will be angels there, praying to God.

She talks about a lot of things I’d certainly never thought about this way, but that actually make sense put this way, and encourage me to have confirmation that such things exist and someone has seen them. The grace of healing is one of these.

Each and every one of us has the grace of healing within us – and it is a wonderful gift God has given us. I see it at work every day. It’s beautiful when I see a mother or father holding a child in their arms and comforting them. The child might have a physical hurt, like a scratched knee, or an emotional hurt like sadness, but the parent, usually unbeknown to himself or herself, is pouring out the grace of healing. It is wonderful to see the grace of healing flow from the parent to the child and to see the child stop crying and go back to playing happily.

There was a whole chapter about angels encouraging us to enjoy life.

I’ve said elsewhere that I hate the question, “What is my destiny?” It seems to imply that life is about one or a few big tasks or goals. My understanding from God and the angels is that each and every one of our destinies is to live life to the fullest. This means living every minute of every day to the fullest and trying to be aware and conscious of every moment and, where possible, to enjoy them all. Your life is today. It’s not yesterday or tomorrow. It’s now. This moment….

In seeing beauty around you, you will appreciate life more, and recognize more the beauty that is within yourself. Appreciating beauty helps you to slow down, and the more beauty you notice, the more beauty you will see. Much of the time we just don’t notice what is around us. We are lost in our thoughts or fail to give any importance or value to the idea of seeing beauty.

Yet another beautiful chapter is called “No one dies alone.” She’s had experiences with seeing people die – and she sees those souls gently being held by their guardian angel and surrounded by other angels, and surrounded by love.

I can go on, and it’s tempting to talk about every single chapter. But this gives you the idea. Lorna Byrne’s words are inspiring and uplifting.

The American edition (which I read) has an appendix at the back with a particular message of hope for America. However, it made me a little sad. This edition was published in 2012, long before the election of our current president. It tells how she sees special gathering angels, gathering people from all over the world, sending them to America. She says that she’s been told that America has a special purpose.

We need to start to pray together. I have been told that praying together is the cornerstone of creating a peaceful world. For far too long religious differences have been a cause of discord and war. Ordinary Americans praying together will allow people of different religions to get to know and understand each other. It will help them to lose their fear of one another, to see just how much they have in common, and to become friends.

I have been told that the first place that big numbers of people of different religions will start praying together regularly is America. This is one of the reasons that the American gathering angels have been bringing people of all religions to this country. It is a part of America’s destiny to help bring all religions together. America will serve as a role model: a beacon of hope for the world. From America this form of praying together will spread across the world, helping to unify peoples and to build world peace.

You can see why this discouraged me in our current climate. However, the chapter does continue with stories of seeing the Angel of Hope working extra diligently in America. I’m going to choose hope and choose to believe that in the big picture, people will listen to God through His angels and forces of good will win out.

And I can’t think of a better way to bolster hope than to read this book.

lornabyrne.com

SimonandSchuster.com

Find this review on Sonderbooks at: www.sonderbooks.com/Nonfiction/message_of_hope.html

Disclosure: I am an Amazon Affiliate, and will earn a small percentage if you order a book on Amazon after clicking through from my site.

Source: This review is based on my own copy, purchased via Amazon.com.

Disclaimer: I am a professional librarian, but I maintain my website and blogs on my own time. The views expressed are solely my own, and in no way represent the official views of my employer or of any committee or group of which I am part.

What did you think of this book?