Last weekend I spent at ALA Annual Conference. It was in Washington, DC, this year, so I drove in early each morning and drove home each night. I had an awesome time, and now I’m going to post my notes and pictures from all the inspiring sessions.

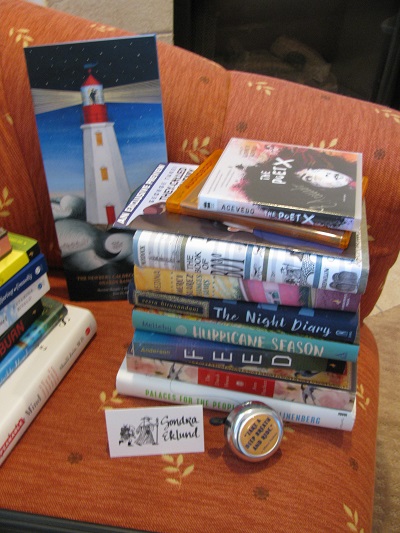

The first event happened on Friday, a preconference sponsored by the Association for Library Service to Children that honored the Honor book winners for various awards — Newbery, Caldecott, Geisel, Sibert, Pura Belpre, and Batchelder Awards. Since the winners get to give speeches but not the Honor books, this is an opportunity to hear from the other honored authors and illustrators and publishers, and I didn’t want to miss it.

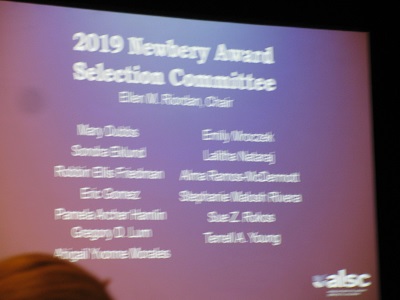

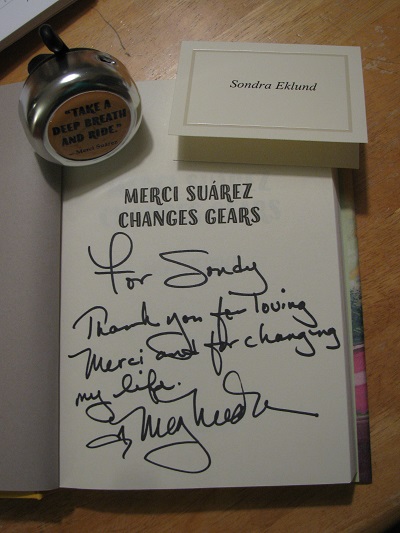

I found two of my fellow Newbery committee members to sit with and we all three chose to go to the sessions where “our” honor authors were featured.

First was an intro session where the 22 honored individuals told three things about themselves. These were fun and light-hearted. I got not-very-good pictures of our Honor authors Veera Hiranandani, author of The Night Diary:

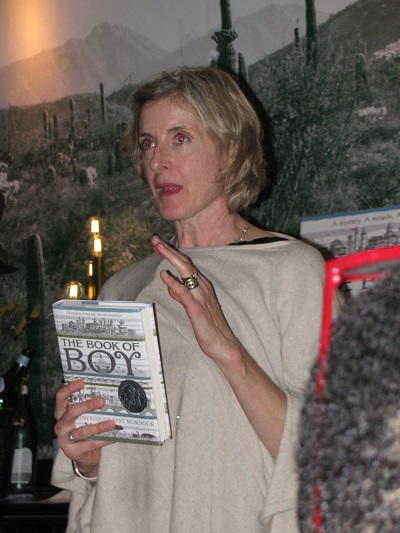

and Catherine Gilbert Murdock, author of The Book of Boy:

Then came lunch, and Caldecott-Honor-winning illustrator Juana Martinez-Neal sat at our table, so we had the fun of getting to know her a little bit.

The first panel after lunch was called “Who Am I? Where Do I Fit In?” The panelists were Leo Espinosa, Belpre illustrator of Islandborn, Claudia Bedrick, Batchelder publisher of Jerome by Heart, Juana Martinez-Neal, Caldecott illustrator of Alma and How She Got Her Name, David Bowles, Belpre author of They Call Me Guero, and Catherine Gilbert Murdock, Newbery author of The Book of Boy.

I’ll write out my notes from the panel.

Question: How do your books resonate with kids who feel they don’t fit in?

Leo: He gets to choose the stories he wants to illustrate. His job is to amplify those messages. He offers reflection and empathy. Some kids see themselves in the books. Some kids feel empathy and want to know these kids who aren’t like themselves. As an illustrator, he has the luxury of adding mini-stories within the big story (such as showing a family with two fathers).

David: Identity and belonging is the core of the story. Kids who are different from a group while simultaneously in that group and feeling solidarity with that group. With light skin, he’s treated differently inside the community. There’s a cognitive dissonance — privileged and oppressed at the same time. Any child can identify with this.

Juana: To fit in is to know who they are, and that’s why she wrote Alma. She couldn’t see herself in picture books. Latinx fit into so many different groups, and that’s why she made Alma. She hopes more kids will see themselves.

Claudia: Jerome By Heart was intentionally about two boys, because if it had been two girls being so tender with each other, it wouldn’t have been so special. In France, two boys holding hands and declaring love is taboo.

We’re shaped in who we are by the responses we receive. This child’s buoyant expression of his personality is not readily embraced by his parents. It shows agency and embracing one’s identity.

Catherine: Her character is an orphan in a goat shed. None of her readers can relate to that, but kids deep dive into it. Kids make it part of them.

Question: Do you write more for reflection or for empathy?

David: He’s primarily thinking of a particular group of students when writing. Kids that need him to write stories about themselves. But other kids need to hear the story as well. The universal comes through the specific.

Claudia: The author of Jerome at Heart was focused on telling the best, truest story about these kids as he could. Every good story promotes empathy. You’ll come away slightly changed.

Leo: He realized the book would be important for Latinx kids. But it’s also important for other kids. He’s read it to Latinx kids, but also to white Mormon kids, and the response is similar.

Juana: She prefers “underrepresented” to “marginalized.” Alma is just about that specific little girl. She hopes this book won’t only be enjoyed by Hispanic communities. We all have names, and we all have families.

Catherine: She had to consider her audience in choosing the words for her book because they need to be understandable for a variety of reading levels.

David: He chimed in that kids are sophisticated thinkers but don’t necessarily have the vocabulary required.

Question: How do you feel about groups you’ve found in publishing circles?

David: The Latinx caucus of children’s publishing tend to gravitate toward each other and there’s a larger community of authors of color. It’s nice to have people helping guide you through it.

Juana: She’ll often spot another author of color across the room.

As far as publishing, editors help her find a balance between what she wants to do and what can be put in a book and what people will understand.

Leo: He doesn’t write his own stories. English not being his first language makes writing scary. He uses illustrations as an international language.

Claudia: Her experience as a small independent publisher is very different from a big publisher. It’s a very different community. There’s a big power difference between indie publishers and the Big Five. She doesn’t hear about “trends.”

Question: Talk about balancing the tension of what we want the world to be and how the world could be.

Catherine: Her big goal is to take readers of all ages back so they’ll say about medieval times: “It was really weird!” If you can appreciate the different values of that time, you can appreciate different values today. We’re part of a big puzzle, and the puzzle is more complicated than we realize.

David: Guero wants the life he lives to be allowed to exist. Guero isn’t looking for perfection — he’s looking for respect for the autonomy of his community. Kids on the border have to grapple with what’s happening to kids their own age.

Claudia: Depicting characters as actors with agency is all about “What If?” So much we live within can be changed.

Leo: He struggled with depicting “the monster” — how to put a really cruel dictatorship into a children’s book? The beautiful part is that the characters are able to defeat the monster.

Juana: She hints at a dark part of history when she depicts Camilla taking a stand.

The second panel was called “Rough Grace.”

Participants in this panel were Veera Hiranandani, Newbery author of The Night Diary, Don Brown, Sibert author of The Unwanted, Gail Jarrow, Sibert author of Spooked!, Brian Lies, Caldecott illustrator of The Rough Patch, and Nathan Rostron, Batchelder publisher of Run for Your Life.

Question: How do you define grace? Rough grace?

Veera: Grace is not an intentional thing. Nisha carries herself with grace in rough times. It’s part of who she is, and it’s not intentional.

Nathan: There are many definitions of grace and graciousness. In the book, set in Sicily, it’s the idea of salvation from on high. What do you do when you can’t rely on outside forces to help? Need to find salvation in yourself and find people to help.

Brian: Rough grace is peace or acceptance through or in spite of adversity. His character’s grace comes because he can’t help being who he is. Souls and stones both get their luster through adversity. It’s not necessarily acceptance, but simply being.

Don: He hasn’t come to a conclusion about grace. There’s no grace when you watch your family drown in the Mediterranean. Or dying in a gas attack. Hemingway romanticizing war was wrong. He’s left not knowing.

Gail: Grace is a gift bestowed on others. The gift of history given to us — we can learn from it. We can learn from the history of The War of the Worlds. There’s a gift bestowed on us from what happened in history. Rough grace is like tough love. Some lessons from history are tough.

Question: How do people go on? How do you wrestle with that as a writer of books for young people?

Veera: I don’t know. Part of it is the not knowing. Nisha’s an observer because she has no choice. In that listening space, an openness comes with that. Taking it in can give you a certain kind of strength. Courage comes in the ability to simply keep moving forward.

Don: It’s a mystery why humanity keeps going. Maybe it’s a basic biological thing to move towards life. It’s inconceivable. As Americans, we look from the outside. The blessing: “May you live in uninteresting times.”

Gail: She also writes about diseases. When you read about people in history who experienced terrible things — some are strengthened and some despair. We can learn from history and those who went through it.

Brian: Resilience. In books, we model resilience for our readers. If you’ve never imagined resilience, how can you learn it?

Nathan: For a kid, the world is always normal. Their author just described daily life. She keeps it very immediate. She has two narratives going — the main character at 6 years old and at 11 years old. Making it immediate can open it up for kids.

Question: Do you self-censor?

Nathan: Self-censors now more than before, from being socially conscious.

Brian: He doesn’t self-censor, but he does self-criticize. Figuring out how to show the dog had died was an example of that. If you don’t see it, you’re asking the reader to care, not making the reader care. It felt more honest to show it on stage. But he didn’t make the reader feel awful — but they see Evan feeling awful.

Veera: She thought about it all the time. More than a million people died in horrific ways during Partition in India and Pakistan. She wanted to show some of the violence. She wanted to include a train with violence — but limited it for a young reader.

Gail: If she has doubts about the accuracy of information, she doesn’t put it in the book. Orson Welles was a notorious liar. Medical mysteries have a lot of gory stuff, but she doesn’t censor.

Don: Do you self-censor because of yourself or other people? I don’t know if I’m being sensitive or I’m being cowardly? Sometimes he can draw around terrible things. The Syrian war began with teens drawing graffiti and they were tortured for it. How to portray that? It’s something he struggles with all the time. How to present nonfiction to kids ages 8 to 13? Older kids can handle literally anything. For them, anything less is phony.

Great difficulty in a book about 9/11 as to how to show someone who jumped.

Brian: Every book is imperfect.

Veera: Kids let in what they’re ready to understand. Don’t let go of the struggle. That’s how you learn.

Don: After writing books, he only sees the mistakes.

Brian: He seeks a 5-year book, a book he’ll be happy with for five years. He has to come to a place of forgiveness. And make sure the next book is better.

Don: Do you like your books?

Gail: I don’t look at my books again.

Veera: I don’t read it again. It’s the readers’ now, not mine.

Question: Talk about the common threads of Fear and Forgiveness.

Nathan: Fear is a big part of Run for Your Life. The boy understands the code of silence. The Mafia’s built it into that society. The structure of fear enables the Mafia. To get over fear, you must let go, and forgiveness is a kind of letting go. Letting go of the silence of the past.

Brian: He purposely avoided reading about the “stages of grief.” There’s an anger aspect to Evan’s grief that wasn’t intentional. Forgiveness comes with time.

Gail: Fear is a big part of Spooked. She told about a couple who fled — and learned that their fear was based on sand. Sometimes fear has no basis. Get info before you act on fear. This story gives you a way to deal with fear.

Don: Fear is in abundance for Syrian refugees. As an example of grace, on a rainy day when he and his wife were visiting a camp, a refugee leant his wife her raincoat. Probably one of her few possessions. That simple act of humanity was one of the most touching things he’s seen in his life.

Veera: Her book is all about fear and forgiveness. People who survived Partition are now in their 80s. It’s up to her generation to preserve the history and begin to heal. That’s why Nisha had a Muslim mother and Hindu father — to be a bridge. Her generation has the distance to do that.

How do you forgive attackers? But now there’s distance, so forgiveness can counteract fear.

Moderator: What does it mean to be human in an imperfect world? Literature reminds us of humanity in the world we live in.

***

So that was the ALSC preconference. The only frustrating part was that several other fascinating sessions were going on in other rooms while I was at those two! But those two were inspiring.