It’s Sonderling Sunday! That time of the week when I play with language by looking at the German translations of children’s books.

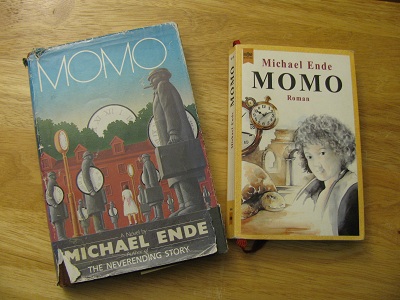

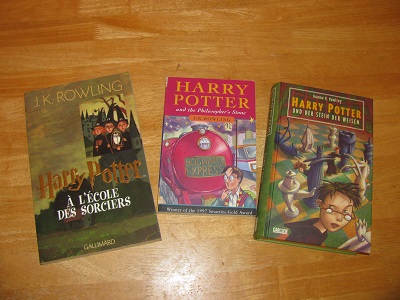

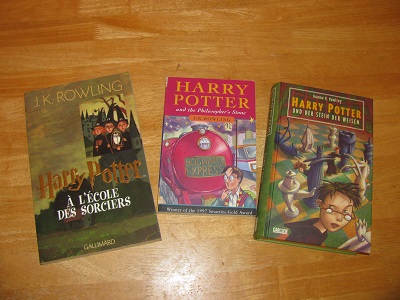

And tonight we get a special bonus. In honor of Harry Potter’s birthday this past week (July 1) and the fact that my son is home from school, with the German edition of HP#1, I’m going to look at the one book I own in English, German, and French, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Harry Potter und der Stein der Weisen, Harry Potter à l’École des Sorciers.

When I started with Harry Potter, I didn’t get very far, but we learned that in French, Dudley has a “was suffering from a small crisis of choler.” And that the Germans don’t thank you in the first line, like everyone else.

Oh, and before I get started, I have a Special Bonus Word of the week. My son and I were learning a new game, and he grabbed the English rules, so I was trying to read along in the German ones, and I learned a brilliant word, Fingerspitzengefühl. It’s translated “balancing act” in the English rules, but it literally means “finger-peak-feeling.” You know, that feeling in your fingers when you put a block on the top of the pile? I love it!

Okay, back with Harry Potter. Think of this as useful phrases in case you’re ever traveling in Germany or France. Have you ever wondered where the phrase books get the phrases they choose to translate? Why not from a children’s book?

I’m starting on page 9 of the British version, page 8 in German, and page 9 in French. (Must be from less front matter that German is the lowest page number. Can’t be that it’s shorter!)

I’m beginning with the line:

“The Potters, that’s right, that’s what I heard –”

= »Die Potters, das stimmt, das hab ich gehört –«

= –Les Potter, c’est ça, c’est ce que j’ai entendu dire…

“Fear flooded him.”

= Angst überkam ihn.

= envahi par une peur soudaine (“overcome by a sudden fear”)

“whisperers”

=Flüsterern

=les gens qui chuchotaient

“snapped at his secretary”

= fauchte seine Sekretärin an

= ordonna d’un ton sec à sa secrétaire

“stroked his mustache”

= strich sich über den Schnurrbart

= se caressa la moustache

“he was being stupid”

= ich bin dumm

= il était idiot

“grunted”

= grummelte

= grommela

(all so onomatopoetic!)

“squeaky voice”

= piepsiger Stimme

= petite voix perçante

“You-Know-Who”

= Du-wei?t-schon-wer

= Vous-Savez-Qui

And this sentence needs to be translated in full so we can use it some day:

“Even Muggles like yourself should be celebrating, this happy, happy day!”

= Selbst Muggel wie Sie sollten diesen freudigen, freudigen Tag feiern!

= Même les Moldus comme vous devraient fêter cet heureux, très heureux jour!

“hugged Mr. Dursley around the middle”

= umarmte Mr. Dursley ungefähr in Bauchhöhe (“hugged Mr. Dursley around in belly-height”)

= prit alors Mr Dursley par la taille et le serra contre lui (“then took Mr Dursley around the waist and squeezed against him”) (Have they no word for “hugged”?)

“imagination”

= Einbildungskraft (“picturing-in-craft”)

= imagination (I might have known. “-tion” words tend to be from French.)

“tabby cat”

= getigerte Katze

= le chat tigré

“the same markings around its eyes”

= dasselbe Muster um die Augen

= Il reconnaissait les dessins de son pelage autour des yeux.

(“He recognized the drawings of his coat around the eyes.”)

“Shoo!”

= Schhhh!

= Allez, ouste !

“pull himself together”

= sich zusammenzurei?en

= reprendre contenance (“regain composure”)

Here’s another nice handy phrase:

“Mrs Dursley had a nice, normal day.”

= Mrs. Dursley hatte einen netten, gewöhnlichen Tag hinter sich.

= Mrs Dursley avait passé une journée agreeable et parfaitement normale.

(“Mrs. Dursley had passed an agreeable day and perfectly normal.” Again, the French are so refined.)

“Mrs Next Door”

= Frau Nachbarin

= la voisine d’à côté

“Shan’t!” (Dudley’s first word)

= pfui

= Veux pas!

Well, I didn’t get far, but I shan’t go any further, because I’ve already spent an hour, pfui!

May my readers have a freudigen, freudigen Tag, or at least one that is agreeable et parfaitement normale!

Buy from Amazon.com

Find this review on Sonderbooks at: www.sonderbooks.com/Fiction/help.html

Disclosure: I am an Amazon Affiliate, and will earn a small percentage if you order a book on Amazon after clicking through from my site.

Source: This review is based on a library book from Fairfax County Public Library.

Disclaimer: I am a professional librarian, but I maintain my website and blogs on my own time. The views expressed are solely my own, and in no way represent the official views of my employer or of any committee or group of which I am part.